Caring for the Carer

overview

In a nutshell

Informal carers are the backbone of many health care systems in the world, yet they are routinely undervalued, overworked, and they feel unsupported and isolated.

Through an in-depth and thorough exploratory research process, I collected rich stories and experiences from not only informal carers themselves, but also professional carers and support workers for informal carers. I discovered that especially carers for people who have dementia struggle with an "always on" mentality, making it hard for them to take time for themselves.

I steadily gained a deeper and deeper understanding of informal carers for people with dementia throughout my research until I arrived at a concise UX Vision Statement that I believe presents a real opportunity to make a difference for carers.

10 weeks

Solo UX Designer

Secondary Research, Interviews, Directed Storytelling, Diary Study, Group Card Sorting, Affinity Mapping, Archetypes, Ecosystem Mapping, Empathy Mapping, Experience Mapping

Figjam, Figma, Behaviour Theories: PERMA Wellbeing Model, Kübler-Ross Stages of Grief

Individual Academic Major Project

introduction

The Challenge

Informal carers for people with dementia often carry an overwhelming emotional and physical burden. Many feel isolated, unsupported, and even guilty when trying to take time for themselves. As a result, these carers feel stretched, like they have to be always 'on-call', and struggle to prioritise their own wellbeing in a society that seems to mostly care about the cared for, not the carer.

The challenge then was to investigate and define the real needs behind carers' experiences in order to identify meaningful opportunities for intervention. I consciously decided to center this project around informal carers because of these reasons, but also because of my personal motivation and values. I believe that caring more about the carers is a very meaningful and worthwhile endeavour, and one that gives me the opportunity to make a difference for people.

How might we find an opportunity that allows the design of a solution to support carer wellbeing?

The Approach

As the project is currently still ongoing, this case study is focused on its first phase, which follows the first half of the Double Diamond process: Discover and Define. I used a mixed-methods approach, combining extensive secondary research with a diverse range of primary user research methods. My aim was to build a deep understanding of the lived experiences of informal carers more broadly at first and later on, I narrowed this down to specifically dementia carers. With this understanding of my target users, I could then synthesise actionable insights, culminating in a UX Vision Statement and three Experience Design Principles that could form a good basis for future design directions.

discover

Secondary Research

Before speaking to users, I immersed myself in secondary research to better understand the context surrounding informal dementia care. I explored a wide range of sources - from academic journals and government publications to personal blog posts, carer forums, and charity websites - gradually building a good understanding of what it means to be an informal carer today.

I went back to secondary research several times throughout the primary research process as themes from conversations with participants emerged, for example to explore relevant behavioural theories and wellbeing frameworks to help interpret and structure what I was learning. Overall, my secondary research included:

- General challenges and lived experiences of informal carers

- Different types of informal carers to start building archetypes

- The PERMA model of wellbeing by Martin Seligman, to frame the impact of caring on wellbeing

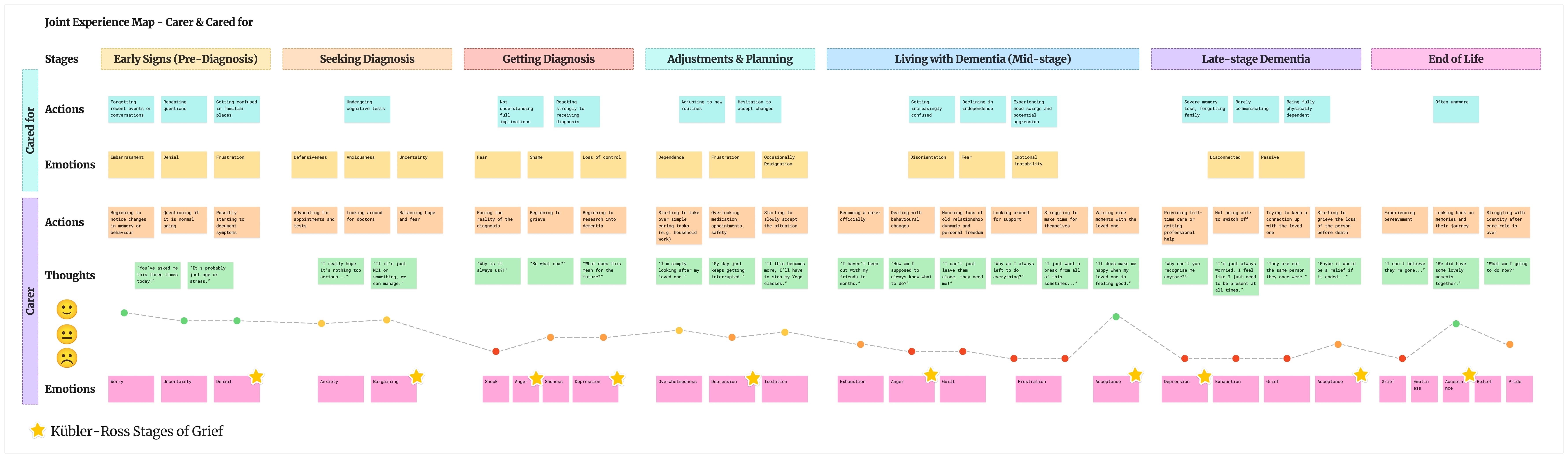

- The concept of anticipatory grief, through the lens of the Kübler-Ross model, the '5 stages of grief'

What stood out most was the emotional landscape of caring - carers don't just face logistical challenges; they're often mourning the gradual loss of the person they once knew, while still caring for them every day. This anticipatory grief emerged as a key theme, deeply impacting their wellbeing and making it harder for them to prioritise their own needs.

Throughout the secondary research process, I tracked findings and surfaced assumptions using a risk-uncertainty matrix. High-risk, high-uncertainty assumptions - such as how supported carers feel by their environment, or the emotional toll of constant presence - became focal points for validation within my primary research.

Primary (User) Research

With a foundation of assumptions in place, I set out to explore the lived experiences of informal carers through qualitative user research. However, from the beginning, I was mindful that this wouldn't be straightforward - carers are often time-poor, emotionally burdened, and, in some cases, vulnerable. Engaging with them ethically and respectfully was essential.

To ensure the research would be safe and appropriate for participants, I went through a rigorous formal ethical approval process with the university. This meant that I couldn't speak directly with informal carers themselves for the first several weeks of the project. Rather than pause my research, I adapted: I used this time to engage with support workers and professional carers, who work closely with informal carers and had rich second-hand insights to offer.

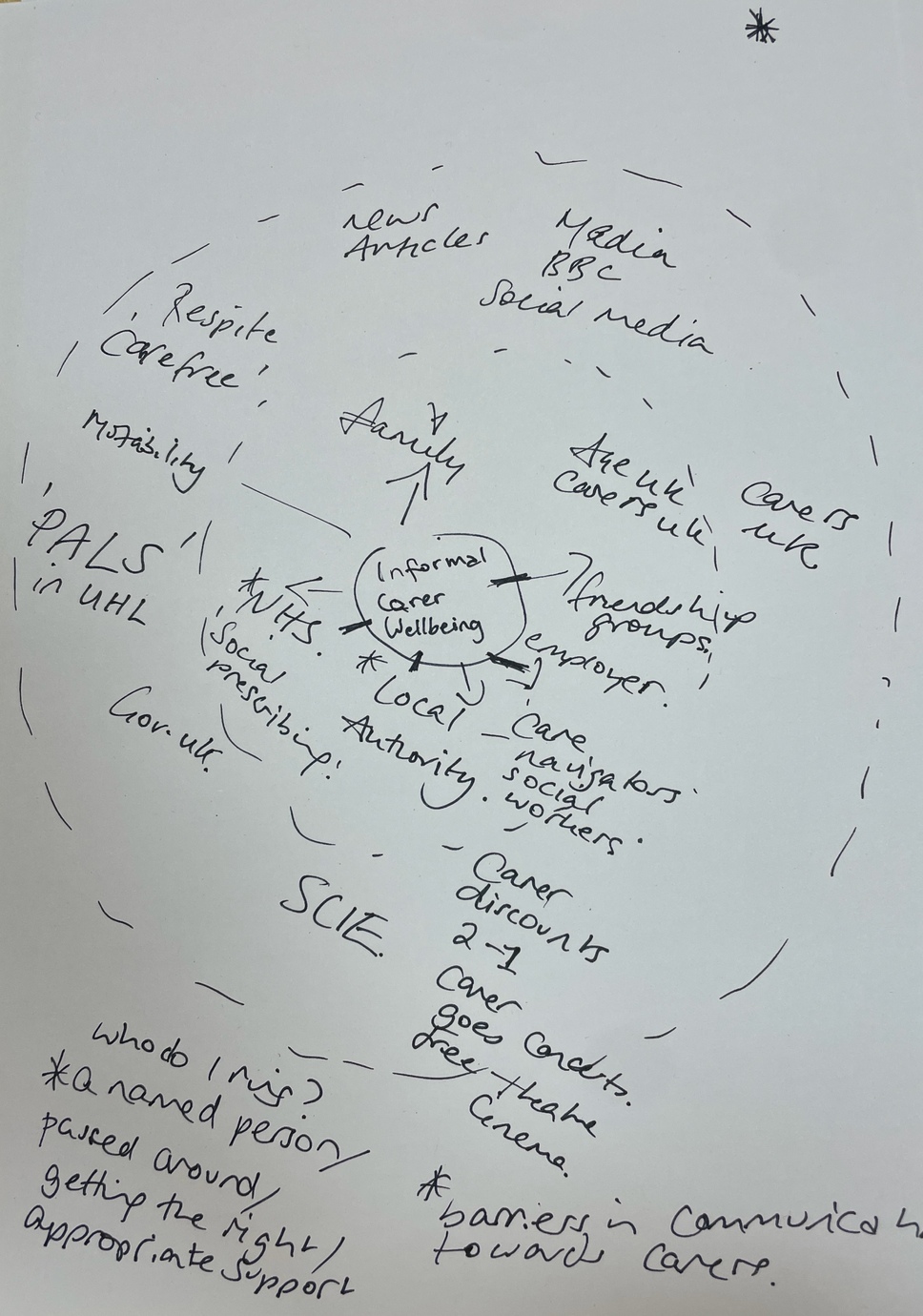

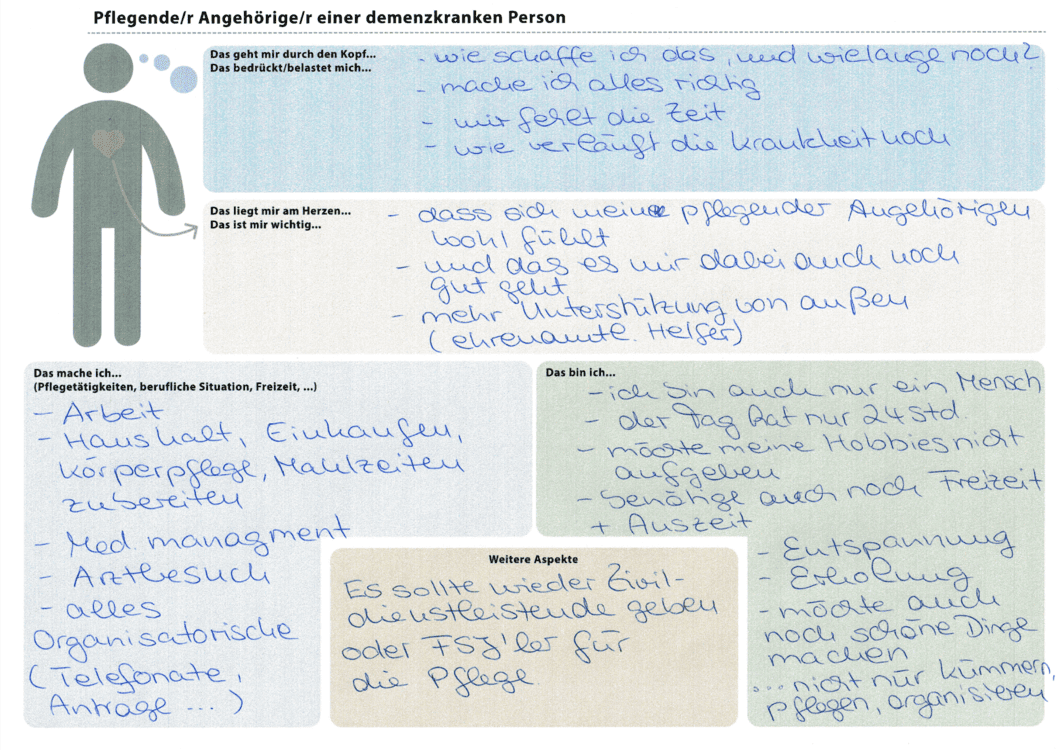

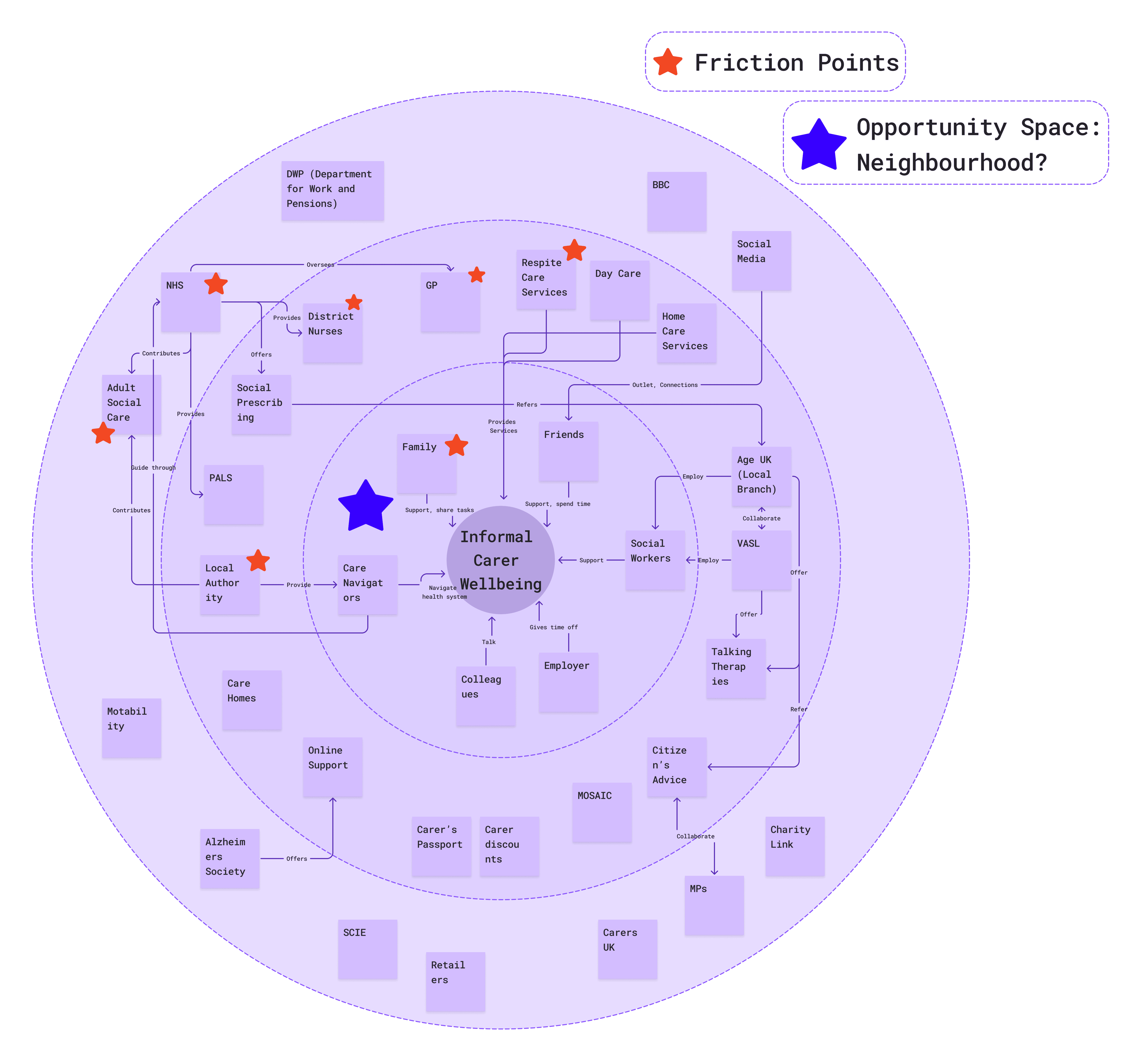

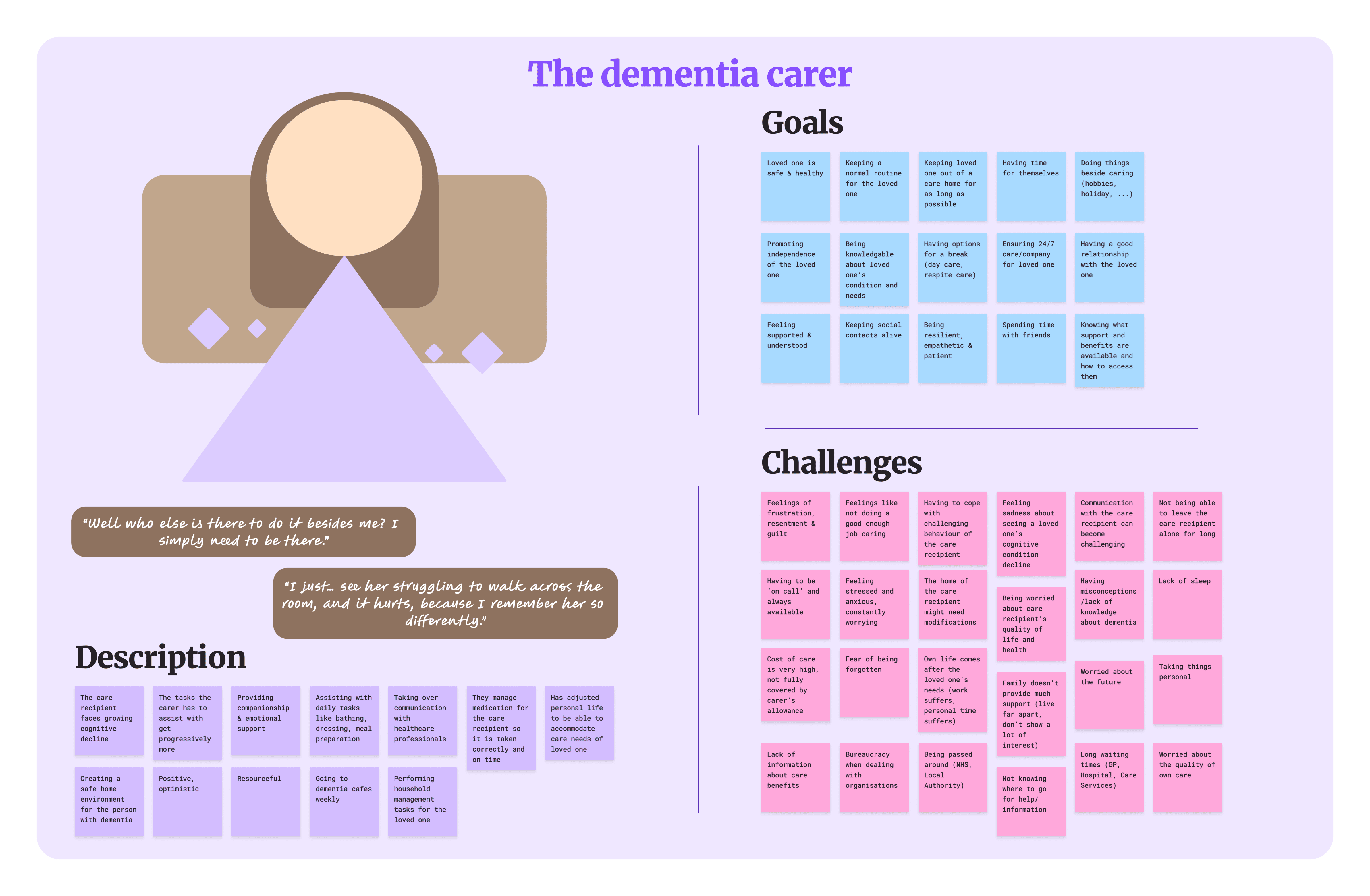

I conducted four semi-structured interviews with support workers for informal carers, including a creative ecosystem mapping activity within the interview to understand carers' wider context and support networks. Similarly, I interviewed five professional carers, supported by a carer archetype-building activity, where we created personas based on archetype templates I developed for this purpose. Throughout these interviews, I started to see a focus emerge on dementia carers as especially emotionally burdoned, so I focused on just the dementia carer archetype.

Interviews with Ecosystem Mapping

Interviews with Archetype Building

Once ethical clearance was granted, I shifted to engaging directly with dementia carers themselves. I wanted to ensure the methods were as respectful and accessible as possible, while still allowing for meaningful, reflective insight. I therefore designed a mixed-method approach, combining rich personal reflective stories with real-time experiences and creative expression.

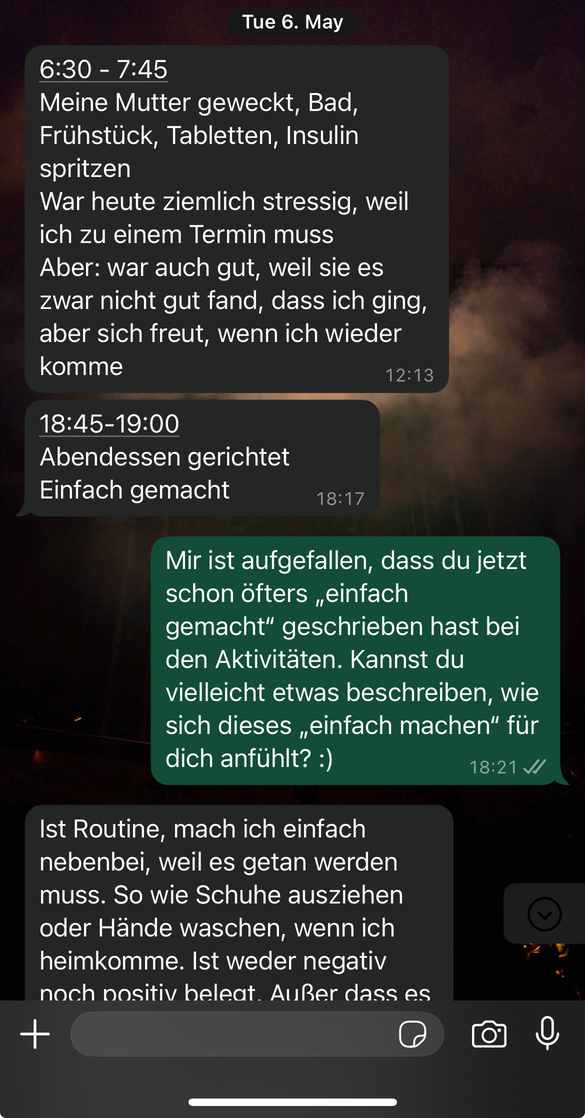

Throughout three directed storytelling sessions, I invited carers to walk me through their daily experiences in their own words, focusing on moments where they felt like they needed a break and time for themselves and what they experienced during these moments. At the same time, I ran a week-long diary study via WhatsApp with an active dementia carer, which offered a lightweight, real-time way for them to share thoughts, moments, and struggles - and allowed me to ask sensitive follow-up questions in a non-intrusive way. Finally, I complemented this with a group card sorting session, using the five PERMA wellbeing categories to explore how different aspects of wellbeing showed up (or didn't) in their caring experiences.

This mixed method approach worked really well. Each method complemented the others: where directed storytelling captured emotional highs and lows, the diary study surfaced day-to-day pressures, and card sorting prompted reflection on needs and values that might otherwise go unspoken.

Directed Storytelling

WhatsApp Diary Study

PERMA Group Card Sorting

define

Making Sense of my Data

Synthesis in this project was an ongoing, iterative process that allowed me to adapt and deepen my focus as new information emerged. I went through two key rounds of synthesis: the first after conducting interviews with support workers and professional carers, and the second following my research activities with dementia carers themselves. This approach allowed me to learn in stages, validating early assumptions and findings while uncovering richer, more nuanced insights from rich, lived experiences as I went.

Round One: Framing the Landscape

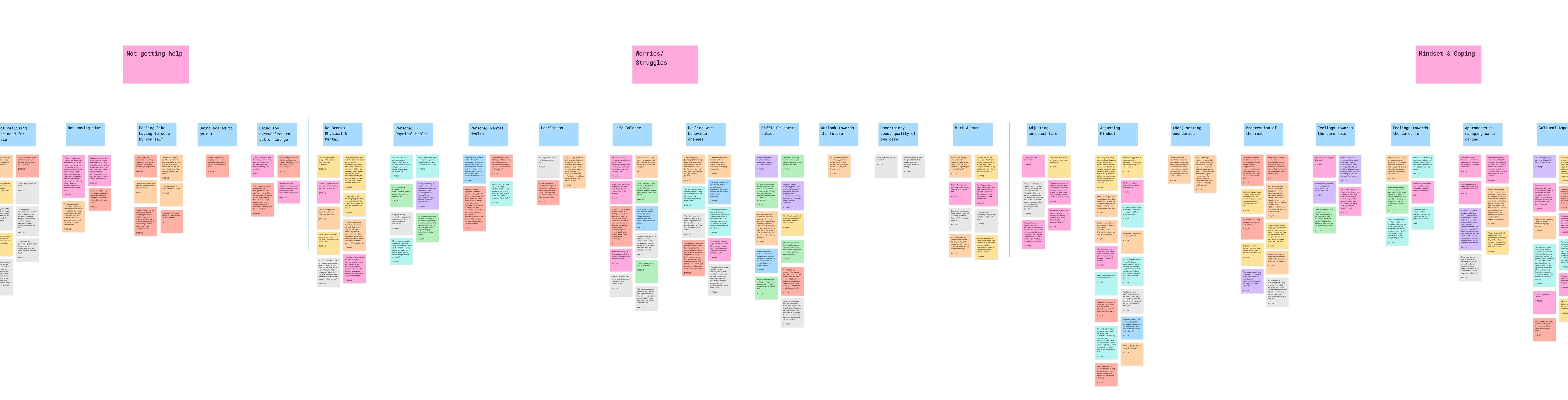

After speaking with support workers and professional carers, I carried out my first round of affinity mapping to start making sense of what I had heard. These participants brought indirect but deeply informed perspectives on the lives of informal carers - I started to see themes emerging around emotional exhaustion, the isolation carers face, and their struggle to maintain a healthy, balanced life around their role as a carer.

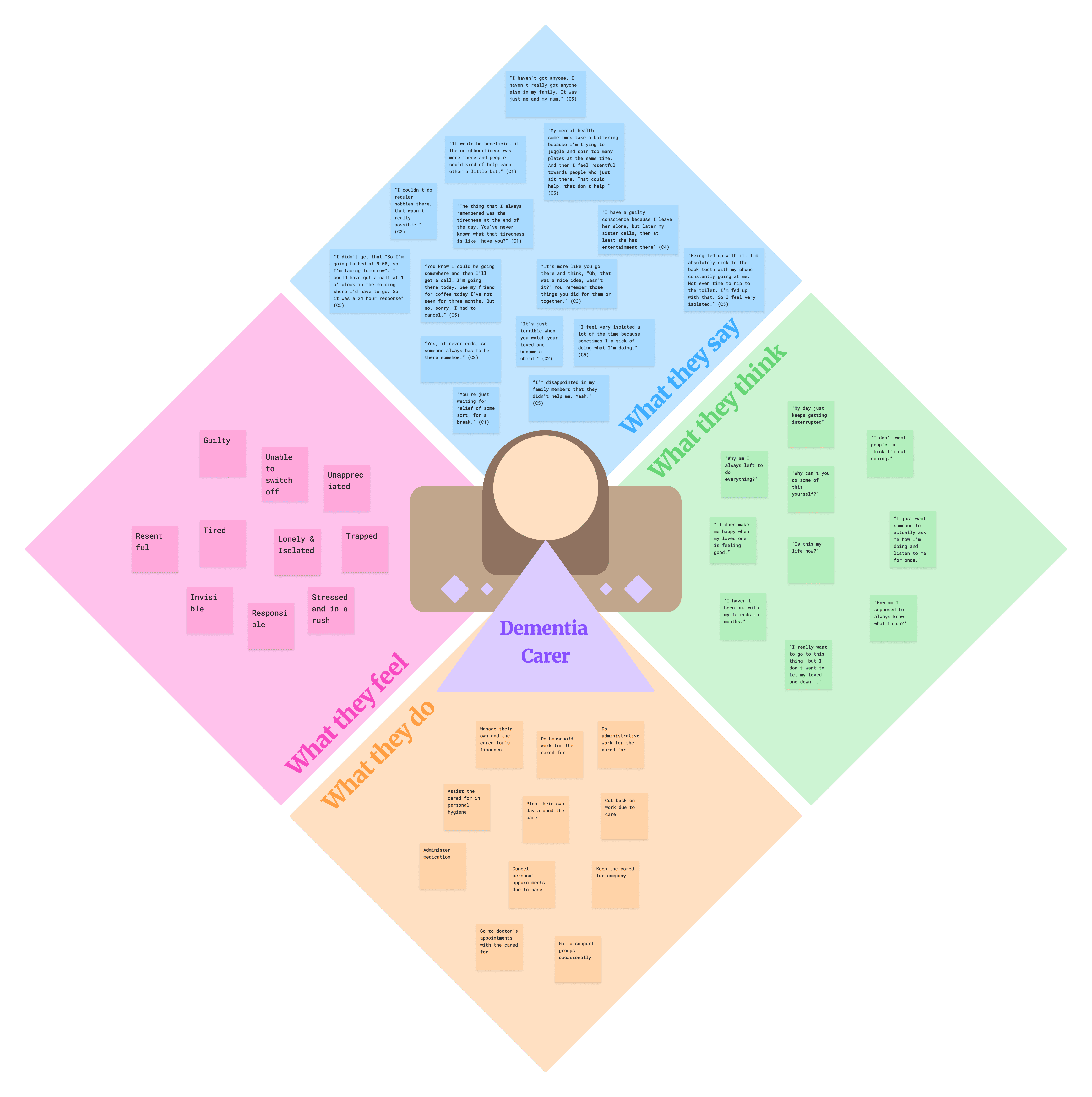

From this synthesis, I also developed two design artefacts in the form of a carer ecosystem map visualising the support network - or lack thereof - that surrounds them, and a dementia carer archetype representing a composite of the needs, goals, and challenges of my target user group. Both of these artefacts were co-created with my participants through the creative activities I conducted with them during the interviews.

With this first round of synthesis, I began shaping an early direction for the next phase of research. A key area of opportunity emerged: the difficulty carers face in taking even short breaks throughout the day. This became the focus of my subsequent research with dementia carers themselves.

Round Two: Deepening the Understanding

With this emerging direction in mind, I had conducted the research activities with dementia carers with the intention to both explore and challenge these early findings and insights. Following this second phase, I returned to affinity mapping, now enriched with first-hand lived experiences. The new data not only validated many of the earlier insights, but also added new emotional and contextual layers - especially around themes like lack of neighbourly support, emotional guilt, and the burden of always being present.

Along with the affinity map, I refined the carer archetype and ecosystem map and created more key artefacts to structure and communicate my findings and insights, including an empathy map to capture carers' thoughts, feelings, behaviours, and frustrations, and a joint experience map highlighting parallel emotional journeys of the carer and the person with dementia.

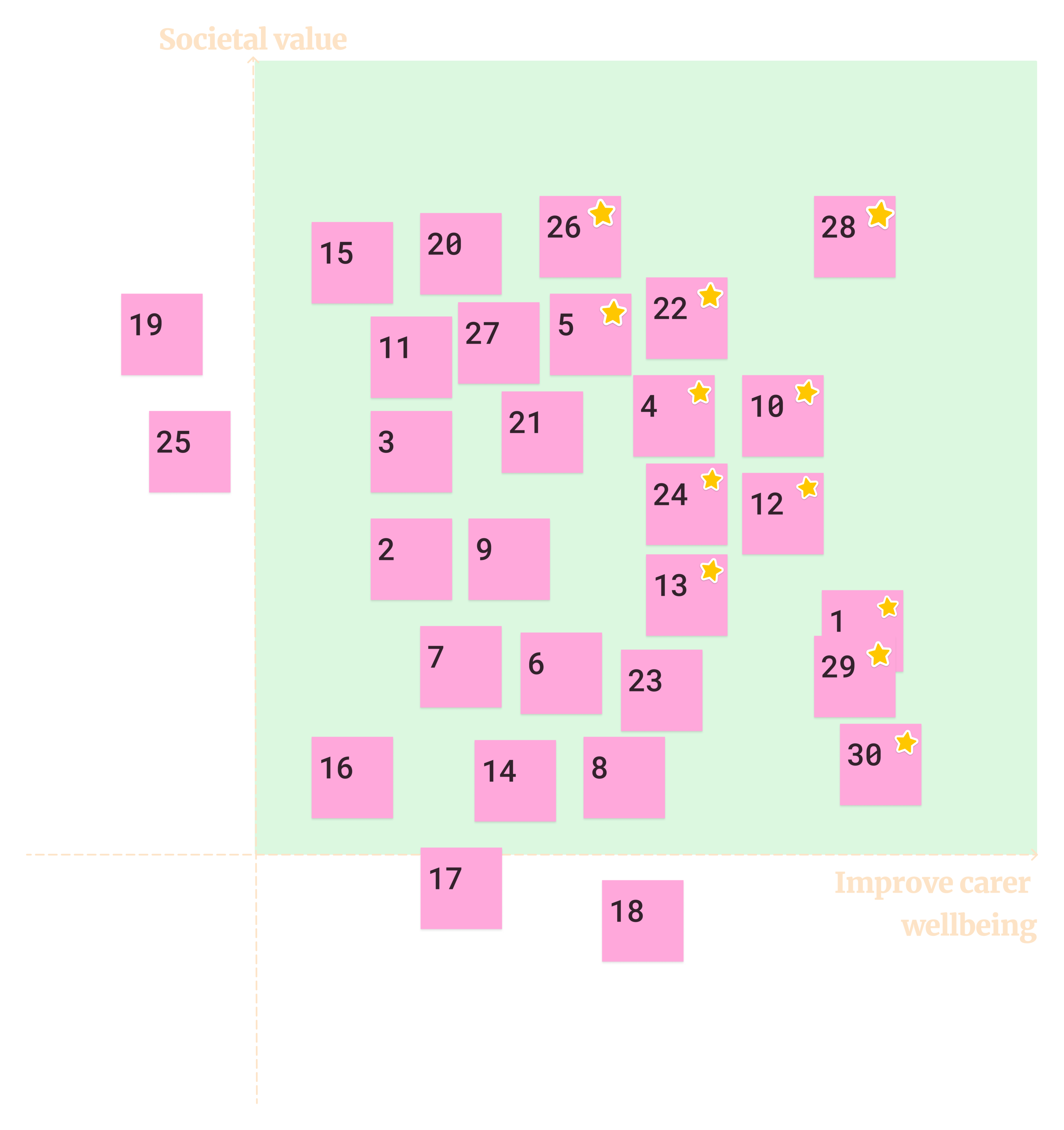

What I found

After two rounds of synthesis, I had extracted about 30 different insights, which I then ranked through a prioritisation matrix and condensed down to twelve key insights. For the purpose of readability within this case study, I have included the three key insights I determined to be the most meaningful and actionable.

"There was four of us. But I got no help from them." (Carer 5)

"Today's neighbourliness has more or less disappeared because of COVID." (Carer 1)

There is a lack of neighbourliness in many communities today, where people often receive little support from around them.

Carers feel like they are on their own with their demanding tasks, having to take on everything themselves and therefore having very little time for themselves, negatively impacting their wellbeing.

"When they start looking after somebody, they start actually grieving, the grieving process. [...] It's like they are starting a grieving process and the acceptance eventually comes in." (Support Worker 3)

Carers experience anticipatory grief when caring for a person with dementia, feeling a sense of loss as the person's condition deteriorates.

Having to deal with grief is difficult and can have a big impact on personal wellbeing, even beyond the cared for's passing.

"Yes, it never ends, so someone always has to be there somehow." (Carer 2)

"But even when she sat there quietly for a few hours, someone just had to be around, and you also had to give her something to drink regularly." (Carer 3)

By feeling the need of being always present, carers create an immensely high physical and mental workload for themselves.

Carers feel like they cannot go away to do things for themselves or cannot switch off, which can facilitate mental health problems and resentment. And when they do go away, they struggle with guilt for not being there all the time.

User Needs emerge

After deriving a wide array of insights, I was able to define a set of user needs:

- Ensuring their loved one is safe, healthy, and well cared for

- Being able to step away occasionally without guilt or anxiety

- Feeling emotionally and practically supported - not just responsible

- Having time for themselves to rest, recover, or pursue other interests

- Preserving a sense of identity and independence outside the carer role

- Staying connected to social circles

- Finding meaning and positive emotion in their relationship with their loved one

Defining the UX Vision

To clearly articulate the direction of the design and create a concise, strong base for a future ideation process, I created a UX Vision Statement that represented the core opportunity I uncovered through my research, taking my insights and defined user needs into consideration. Alongside it, I defined three Experience Design Principles to guide ideation and decision-making going forward. These principles serve as a constant reminder to stay user-centred and as a framework, helping me evaluate future concepts against what matters most to my target users.

There is an opportunity for a product or service for informal carers of someone with dementia who want to be able to occasionally take time for themselves to prioritise their own wellbeing, but feel stretched by the constant demands of caring and isolated and unsupported in their community, impacting their ability to step away confidently without worry or guilt.

Trustworthy

Carers can rely on it to ensure their loved one is safe and well cared for.

Flexible

Carers can get the specific support that they need within their unique situation.

Supportive

Carers feel emotionally and practically supported by a genuine, understanding network.

reflections

This project has been a meaningful and very challenging journey in more ways than one. Gaining ethical approval delayed my access to participants, but I adapted by sourcing valuable insights from support workers and professionals early on. I'm especially proud of how I was able to maintain a rigorous, ethically sound process throughout all the challenges I faced while also managing multiple university projects simultaneously.

Emotionally, this was one of the most human and impactful topics I've explored. I was especially struck by the concepts of anticipatory grief and the that of lacking neighbourliness - as someone raised in a small village where everyone knows everyone, it was almost a given for me that people support and help each other, so finding out my participants didn't experience this came as a big surprise to me and challenged my basic societal assumptions. Now, it deeply informs my mindset and design vision.

Coming from a computer science background, I'm used to structure and logic - and this project has challenged me to become more comfortable with ambiguity and the messiness of the exploratory research process. That said, I was able to use my analytical mindset as a strength as well: I was able to manage complexity, make confident methodological decisions, and identify patterns within messy, human data while never losing focus of the bigger picture.

what's next?

This case study represents the first half of my UX Master's Major Project, focusing on discovery and definition. The next phase - ideation, prototyping, and testing - builds on these insights to develop a user-centred design solution for dementia carers. Click on the "Next Case Study" button below to see the outcome of this final phase of the project.